At a time when Major League Baseball was a closed door to many of the finest ballplayers in the country because of their skin color, a critical chapter in the history of emancipation was written in Indiana.

On May 2, 1920, the first pitch was thrown in a Negro National League game at Washington Park in Indianapolis. The home Indianapolis ABCs defeated the American Giants, 4-2.

The founding of the Negro National League a century ago this month is being celebrated as a symbol not only of a breakthrough in the showcase of black talent, but as a milestone in the big picture of the civil rights movement.

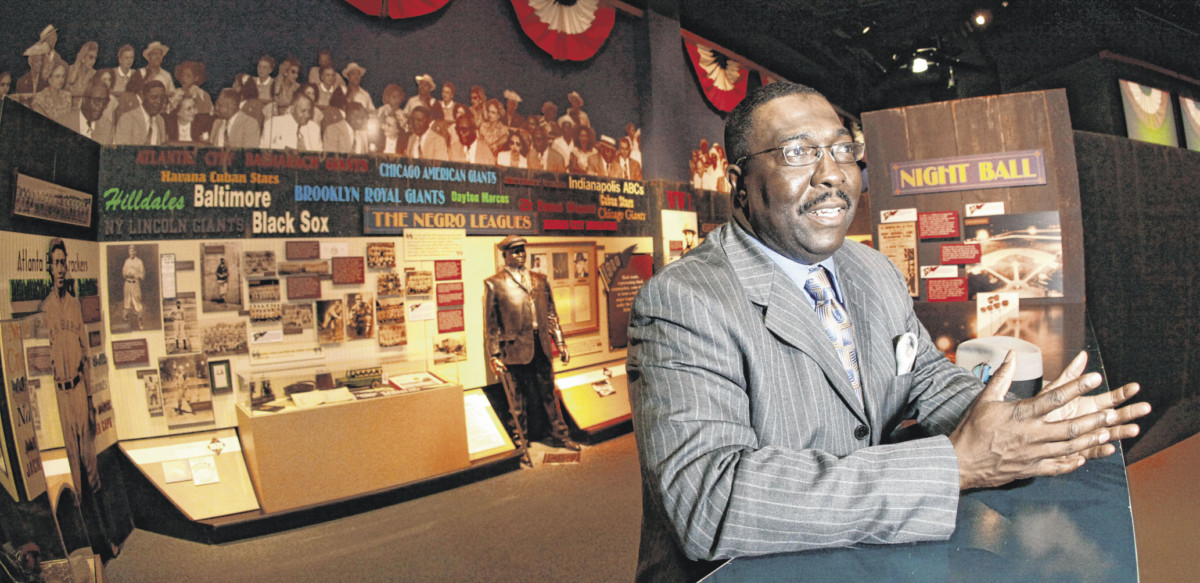

“It was the beginning of social justice,” said Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City in a recent interview. “It was a shameful period in American history. Out of this rose a story of desegregation.”

Kendrick is the custodian of the past. As part of a year-long centennial tour that began with receipt of a $1 million grant in February, Kendrick was scheduled to appear in Indianapolis May 2 to put the spotlight on that 100-year-old game.

Only the COVID-19 pandemic grounded him. No Indianapolis visit. No tour for now.

The Negro National League, followed by the Eastern Colored League, and the Negro American League over the next 30-plus years, was created at a Feb. 13, 1920, meeting at a YMCA in Kansas City.

The museum is located at 18th and Vine Streets in Kansas City where jazz clubs once flourished as the heartbeat of black social life in the community. The mission is to preserve the legacy of the pioneering men relegated to the shadows when white baseball snubbed them.

“We are saving as much history and Americana as we can,” Kendrick said.

It was Rube Foster’s vision, however, that may have saved them all.

Beginnings

Foster, whose given name was Andrew, brought the weight of his formidable pitching reputation to his organizing efforts.

As an early indication that accurate statisticians were in as short supply, something that long plagued black baseball, it was once stated Foster was 51-4 season in 1905, but later review downgraded the mark to 25-3.

Foster wanted African-Americans to take control of their own destiny. His aim was “to create a profession that would equal the earning capacity of any other profession and do something concrete for the loyalty of the Race.”

The word “Race” was capitalized intentionally.

Magnates emerged from the organizational meeting with eight charter teams: Foster’s Chicago American Giants, the ABCs, the Cuban Stars, Dayton Marcos, Chicago Giants, Detroit Stars, Kansas City Monarchs, and the St. Louis Giants.

When the meeting concluded, Foster declared, “We are the ship, all else the sea.”

Foster, a burly man, whose mental health deteriorated, died in an asylum at 51 in 1930. But he was heralded as “The father of black baseball” and inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1981.

Honors that came long after his death would have stupefied Foster.

In 2010, the United States Postal Service issued a two-stamp set, commemorating the Negro Leagues. One of the 44-cent stamps featured Foster, jaunty in sports jacket and tie with a Jeff cap perched on his head.

What Rube wrought

Great black players found homes on big-city teams as Foster’s vision came alive.

Yet earlier, as great white ballplayers like Cy Young, Walter Johnson, Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth flourished, some of the greatest players competed in obscurity.

African-Americans were blocked from the majors, relegated to second-class hotels, refused service at restaurants, threatened by lynchings, tormented by white-hooded members of the Ku Klux Klan and subject to police abuse. It was sometimes difficult to tell the Civil War had been over for 55 years.

Negro Leagues baseball offered dignity, high-caliber competition and appreciative fans. Nevertheless, without television and overlooked by big-city mainstream newspapers, most black players were word-of-mouth stars among their own people, heroes at the intersection of fact, folklore, and mythology.

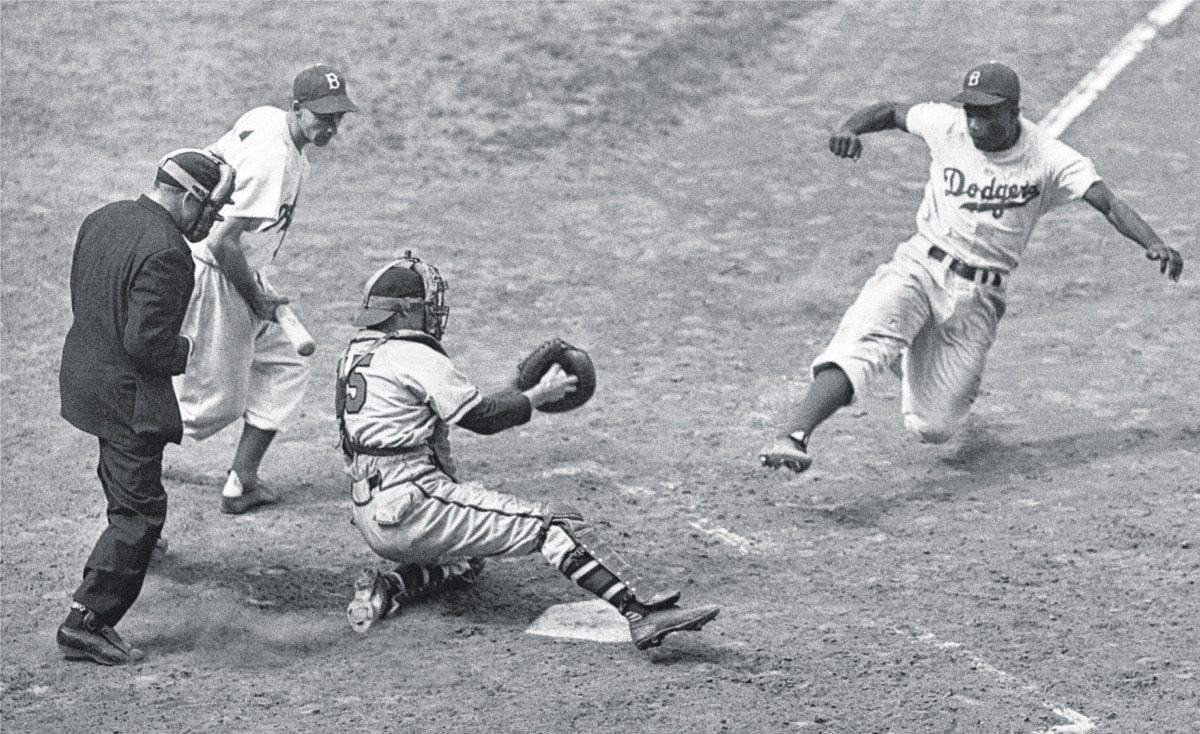

Jackie Robinson is nationally famous for breaking baseball’s modern color line with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. There were black major leaguers, however, in the 19th century.

Brothers Moses Fleetwood Walker and Weldy Walker are acclaimed as the first African-Americans to play in the big leagues for the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884 of the International League when that was a major-league circuit. The Society for American Baseball Research suggests a William Edward White played one game for the Providence Grays in 1879, though he passed for white.

Moses Walker, who signed before his brother, and played 42 games, was subjected to intense racial discrimination.

The Walkers were victimized by the prejudice of famed hitter Adrian “Cap” Anson. His Chicagos were scheduled to play an exhibition versus Toledo on Aug. 10, 1883. When he discovered the team had a black player, he protested. Walker’s manager and teammates supported him.

“We’ll play this game here, but won’t play never no more with the n—- in,” Anson said.

This episode triggered baseball’s off-the-books, firm policy prohibiting black players in the majors until Robinson’s debut.

Second baseman Frank Grant was the regarded as the finest black player of the 19th century. Shortstop John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, catcher Louis Santop and outfielder Cristobal Torriente were already established by 1920. All of these underexposed stars are members of the Hall of Fame.

Oscar Charleston may have been better than any of them. Although Charleston spent 21 years in the Negro Leagues with a variety of teams, he was Indianapolis through and through.

He was a member of the Indianapolis ABCs in his hometown, starting in 1915. Charleston was a dazzling center-fielder, with a lifetime .339 batting mark, and hit home runs that were said to travel more than 500 feet.

“Oscar Charleston has compiled one of the greatest records in baseball,” said Indianapolis Clowns owner Sydney Pollock, who hired him as manager, “and is well-known to old-timers as one of the game’s greatest natural athletes.”

If Pollock was a loud voice in the Oscar Charleston Fan Club, Buck O’Neil was the leader of the chorus.

The next generation

Negro Leagues teams rented Major League stadiums and conducted their own All-Star game, the East-West Game. Some 35,000 fans might attend, many of them white, determined to see how good these black players were.

There was plenty to see.

Martin Dihigo was a .300 hitter who also pitched and is in baseball halls of fame in Cuba, his native country, Mexico and the United States. In one Mexican season, Dihigo finished 18-2 with an 0.90 earned run average. In Cuba he was called “The Immortal.”

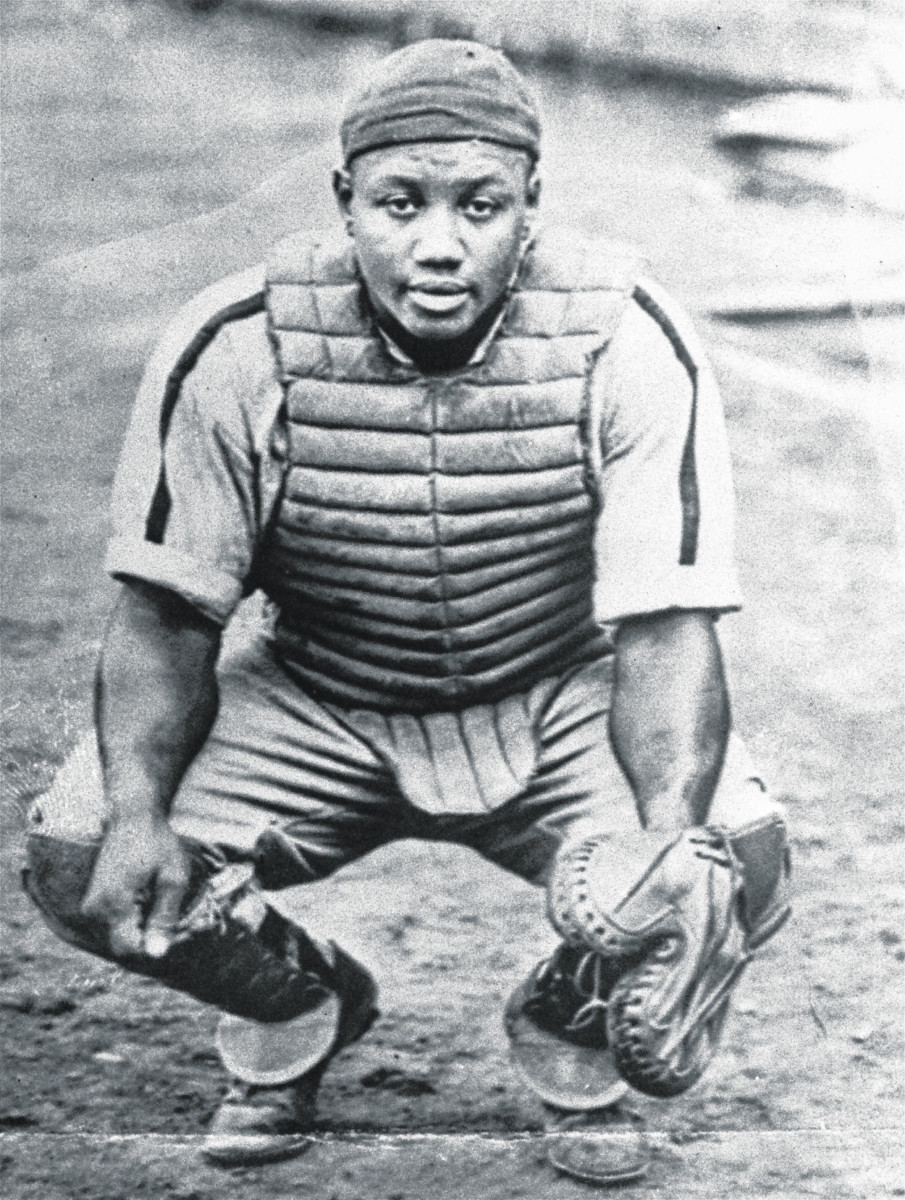

Theodore Roosevelt Radcliffe was known as “Double Duty” because he caught one game and pitched the other in a double header. In fact, Radcliffe, who lived to be 103, pitched in three East-West games and caught in three.

Slugging Buck Leonard played with the Homestead Grays from 1934 to 1950, hitting .320. In his Hall of Fame acceptance speech Leonard addressed the elephant in the room, being banned by the majors.

“We in the Negro Leagues felt like we were contributing something to baseball, too,” Leonard said.

James Bell broke in with the St. Louis Stars in 1922. Originally a pitcher, Bell was nicknamed “Cool” for his demeanor after a clutch strikeout of Oscar Charleston. He added “Papa” because he felt “Cool Papa” sounded cooler still.

A .328 hitter, Bell has often been called the fastest runner in baseball history. When they roomed together, famed hurler Satchel Paige embellished Bell’s speed legend by saying Cool Papa could flick off the light switch and be under the covers before the room darkened. The story was partially true because the lighting system was faulty and flickered.

Less apocryphal, third-baseman Judy Johnson, another Hall of Famer, testified about the impact of Bell’s fleetness.

“You couldn’t play back in your regular position, or you’d never throw him out,” Johnson said.

The king of Negro Leagues sluggers was Josh Gibson, plucked for the Homestead Grays as a naive teenager by one of the league’s sharpest owners, Cumberland Posey.

At 6-foot-1 and 210 pounds, Gibson’s strength was Herculean. Playing year-round in other countries and barnstorming, it was estimated Gibson hit more than 800 home runs.

Gibson was said to be bitter the majors chose Jackie Robinson instead of him as the first 20th century African-American, but Gibson died at 35 from a brain tumor only months before the majors integrated.

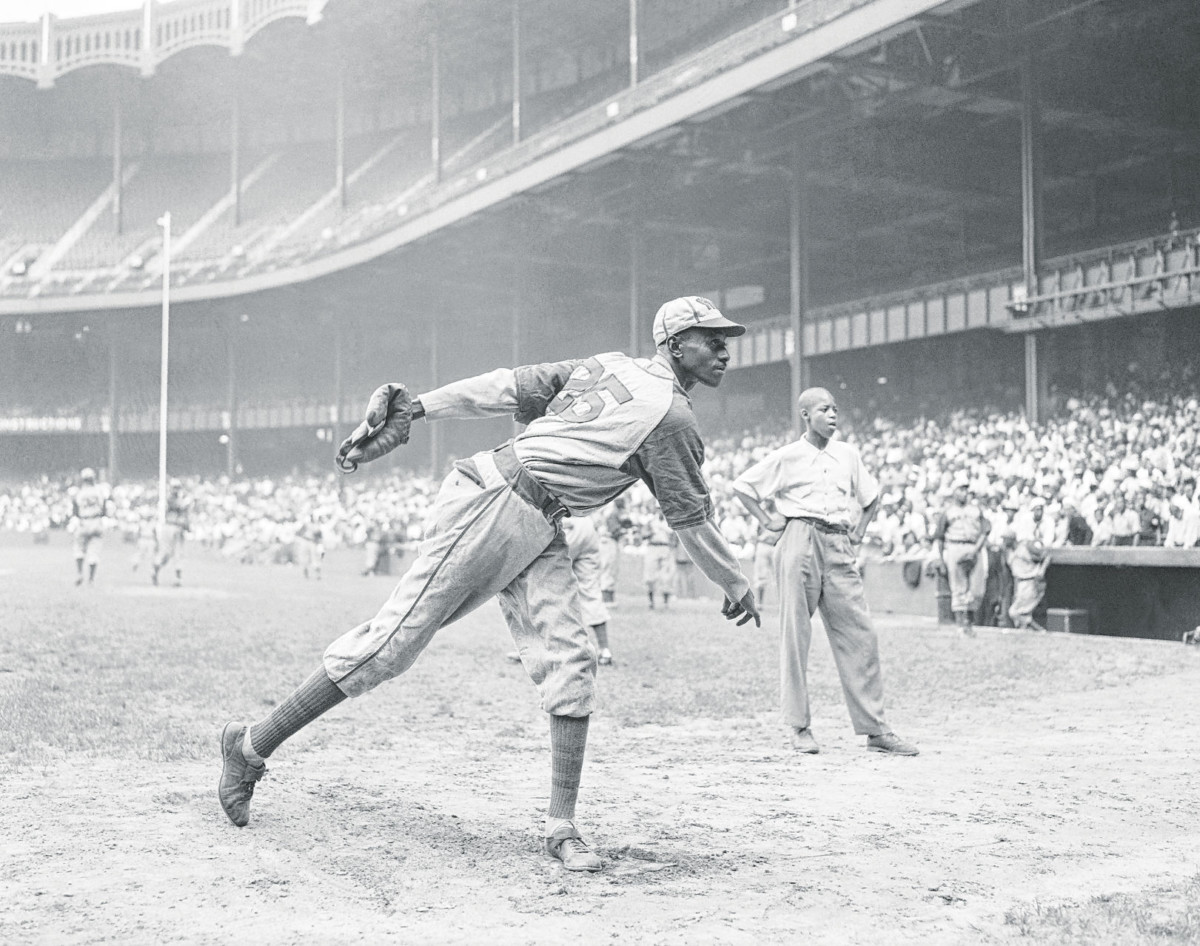

There was no one like Satchel Paige. Clever, witty, a showman with style, Paige was a genius at self-promotion and striking out batters. He was a man of mystique, hiding his true age.

Eventually, Paige’s birth certificate was dug up in Mobile, Ala., showing he was born July 7, 1906. The long-limbed Paige threw fastballs faster than cars moved in his youth and named some of his junk pitches. Periodically, he ordered all fielders except his catcher to sit down while he struck out the side.

Paige claimed about 2,000 victories with Negro Leagues clubs, in exhibitions and for touring all-star teams He recorded funky rules for living, the most famous being, “Don’t look back, something might be gaining on you.”

After African-Americans fought for their country in World War II, black newspapers ramped up pressure on the majors to hire African-American players.

Several younger players were signed, disappointing Paige, serendipity whistled and at 42 in 1948 he joined the Cleveland Indians as a relief pitcher. He finished 6-1 and the Indians won the World Series. In 1952, Paige made the American League All-Star team for the St. Louis Browns.

In 1965, Oakland A’s owner Charlie Finley signed Paige for one game. Paige, 59, sat on a rocking chair in the bullpen until summoned for three scoreless innings against the Boston Red Sox.

Before he died at 75 in 1982, reflected.

“I had more fun and seen more places with less money than if I was Rockefeller,” Paige said.

The truth will come out

Negro Leagues stars went to their graves believing their exploits were forgotten. They were wrong.

In 1966, Ted Williams, the legendary .344 hitter for the Red Sox, spoke up for them during his Hall of Fame induction speech.

“I hope that some day the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way could be added as a symbol of the great Negro players that are not here only because they were not given the chance,” Williams said.

In 1970, Robert Peterson’s breakthrough book, “Only The Ball Was White” was published. That was followed by ground-breaking works written by John Holway.

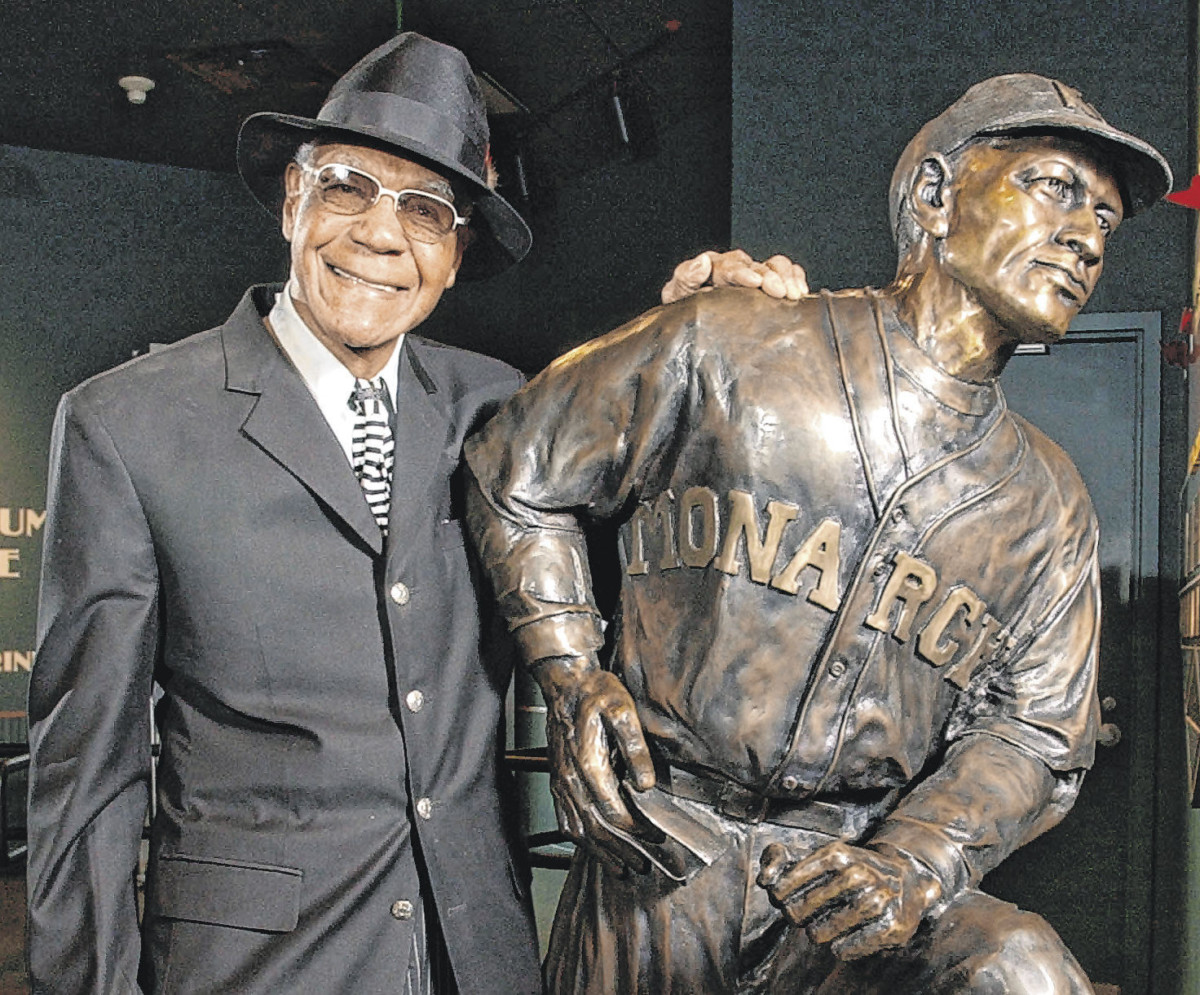

Documentary maker Ken Burns provided in-depth attention to the Negro Leagues in his 1994 film “Baseball.” Burns turned Buck O’Neil into a TV star as an eloquent spokesman for the game he lived with the Monarchs and about the times he lived in between 1937 and 1955.

O’Neil, long the face of the Kansas City Monarchs as a player and manager, spearheaded creation of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in 1990. Awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom before his death at 94 in 2006, O’Neil was considered a local Kansas City treasure.

Once, while seated at a small table in the museum, O’Neil spoke about the sad years of segregation and his satisfaction with his late-in-life work.

“That’s why I wanted the museum here,” O’Neil said, “so what happened would never be forgotten. To understand man’s inhumanity to man, that’s been a terrible thing. There was nothing fair about it at all.”

Hank Aaron, 86, spent three months with the Indianapolis Clowns as a teenager. The late Ernie Banks was managed by O’Neil in Kansas City for two seasons before joining the Cubs. Willie Mays, 89, played for the Chattanooga Choo-Choos and the Birmingham Black Barons while still in high school.

George Altman, 87, who spent three months with the Monarchs in 1955 at the tail end of their run, also came under the sway of O’Neil.

“Buck O’Neil was my first real mentor. I started thinking about what I might be able to accomplish in baseball,” said Altman, who lives near St. Louis, “and the Monarchs gave me the opportunity to play every day.”

Since baseball took Ted Williams’ words to heart and selected Paige as the first Hall of Fame inductee from the Negro Leagues, 35 players have been so honored. Thirteen of them were Monarchs at one time.

The Negro Leagues passed away because the best players were all welcomed into the majors. Those of that bygone era can be compared to World War II veterans, age taking them swiftly now.

“There’s no question about it,” Kendrick said. “We knew from the outset this was a race against time. It wasn’t a matter of if they were going to be gone. That’s why this museum is so important.”

Like Rube Foster, Bob Kendrick believes he and the museum are doing something special for the Race.