It took just one goal for the grandest American hockey hero to etch his name on the history of the sport, but 40 years later, the fame still clings to Mike Eruzione.

Enduring proof that life can change in an instant, the man who served as captain of the 1980 U.S. Olympic gold medal hockey team and who scored the winning goal against the Soviet Union in Lake Placid, Eruzione is the personification of what has endlessly been proclaimed the greatest American sporting event of the 20th century — and of all time.

If you were there and saw it — as I was — you have no doubt that is true. If you were alive and older than a third-grader, you never forgot.

After the group of underdog college kids fended off the challenges of every world hockey power, they visited President Jimmy Carter at the White House. This February, in a precoronavirus reunion, the team met with President Donald Trump.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]

Even leaders of the free world don’t mind basking in the glory of the seemingly long-past but never-gets-old achievement of the skaters who were 20-somethings then and 60-somethings now.

Coach Herb Brooks, the work-’em-till-they-drop coach, has passed away. Many of the players had distinguished National Hockey League careers and even won the Stanley Cup.

Eruzione was the oldest, then 26, the leader, if not the most skillful, of the players and in a certain manner never stopped being the spokesman for the team, the out-front guy who more than any of the others and for all Americans froze the miracle in time.

This was more than winning "Dancing with the Stars," bigger than winning another kind of annual sporting championship, an occasion where the spotlight never stops shining.

For this anniversary, Eruzione, who has never stopped accepting invitations to speak about what this unique band of Americans achieved, put his thoughts on paper, too, penning a book about the fabulous winter run and his life called "The Making of a Miracle."

Now that the NHL is playing again, seeking to wrap up its 2019-20 season in the summer in the sealed-off outposts of Edmonton and Toronto, it makes sense to talk hockey in August.

"I never wanted to write a book," Eruzione said by telephone as he drove to his home in Winthrop, Massachusetts, on the outskirts of Boston. "I did it for my grandchildren. I wanted my grandkids to know my life wasn’t just about one goal, one shot."

The goal

It would be easy enough to make that assumption, although no one’s life can be summed up so neatly or briefly.

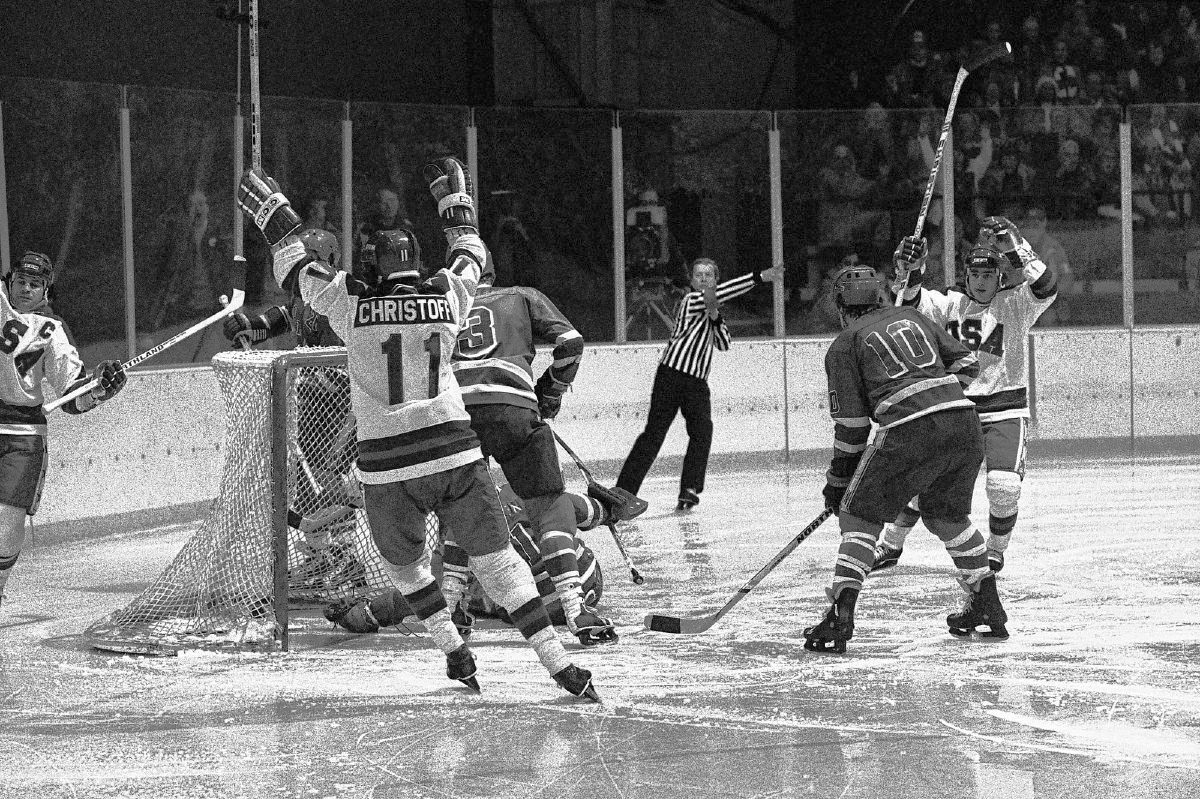

Eruzione’s famous goal was scored in the upstate New York Olympic Field House with 10 minutes remaining in a semifinal game of the 12-nation Olympic tournament against the perennial champion and heavily favored Russians.

In front of 8,500 screaming, partisan U.S. fans, he unleashed a slap shot that beat Soviet goaltender Vladimir Myshkin, the world went crazy and suspense built with the noise and intensity of a jet increasing speed for takeoff.

"Ten minutes," Eruzione said of the interminable wait for the buzzer to sound. "It was a long 10 minutes."

Unless you were Brooks and his coaching staff or an insider with the team that had played together for a year’s worth of exhibition games, nobody believed the young Americans could win this, true amateurs over the pretend amateurs.

Me among them, a bit dizzy because of all the players, it was Eruzione whom I knew the best. We both attended Boston University. I was three years older but covered the Terriers hockey team when he was a freshman.

We were also both from the near north side of Boston’s outskirts. Not the North Shore where the beaches led to dips in the Atlantic Ocean, but he from Winthrop and me from Chelsea, where my mother grew up, and Revere, where my father was raised. These were working-class towns near Logan Airport, almost spilling into one another.

Eruzione is Winthrop’s favorite, so he still lives there, and the blocks near his house are filled with other younger Eruziones’ homes now that Mike’s parents and older relatives are gone.

Late in 1979, when my newspaper assigned me to cover the U.S. hockey team in Lake Placid, I never dreamed I was being handed a pass to the most amazing sporting event I would ever witness.

When told to find someone to feature leading up to the Games, I chose Eruzione because of our Boston overlap, not because I counted on him authoring more drama than playwright Eugene O’Neill.

There we sat in a Madison, Wisconsin, hotel room hours before the Americans played a game against the University of Wisconsin. It was the 57th prep game for the Olympians, Eruzione was trying to coax a broken hand into healing and Brooks and Mark Johnson, the key scorer for the club, had both already spoken about Eruzione’s intangibles, hustle and leadership that made the guys listen to him.

Eruzione’s first hockey game, as a 9-year-old, was played in Winthrop. His last hockey game was played representing the United States of America with cries of "U.S.A." sung in his ears by adoring fans.

While we talked, the TV set showed "Love Boat." Eruzione gripped his pillow tightly and twisted it into knots. I recall that image clearly, almost as if that Mike is still the boyish fellow, innocently, but expectantly awaiting the moment of fame looming.

No one could realize I was sitting next to an 8.0 earthquake about to shake the earth.

Perhaps the most telling thing Eruzione said was, "I think out on the ice, I’m a smart hockey player. I’m not going to take the puck from one end of the ice to another. Still, I’ll score my share of goals."

Mike Eruzione then had muscled arms, the better to push off defenders trying to cut off his rushes to the net. He said he ran up big phone bills talking to relatives in Massachusetts. He painted houses in the offseason. His father was both maintenance mechanic and bartender. The Eruziones understood hard work.

He laughed slightly when mentioning teammates thought he was a guy who was just "high on life," making the comment before it became a cliche.

And then he scored the goal and has been high on life ever since, it seems.

Still the man

Eruzione’s renown and identification with the goal and the hockey team have lasted.

Some actors have played him in movies. He has been an active fundraiser for his alma mater, Boston University, was an assistant coach for the BU hockey team for three years, and he delivers motivational speeches. There is a Mike Eruzione website explaining how he can be hired by a corporation for $20,000 or $30,000 per talk.

I have rendezvoused in conversation with Eruzione, every 10 years or so. He is always upbeat, sounds much like the same guy from college days, is very much aware of his place in American Olympic history, but is neither boastful nor brash about it.

He has said, "The 1980 Olympics, it is not the most important part of my life." Eruzione means it does not measure up to family. "It hasn’t changed me. It has given me the opportunity to do so many things."

Unlike the movie "It’s a Wonderful Life," which is fiction, Mike Eruzione has lived a wonderful life. There is no mystery about that contained in his book.

"My kids read it and liked it," Eruzione said in our recent talk. He knows the hockey team touched millions of Americans with its spirit and triumph. "It was a great event for a lot of people."

Of course, he remains proud of being part of the magic and is someone who very much contributed to making magic.

"How can you not be?" Eruzione said.