Clomping around in his raincoat, trusty spotter next to him, Steve Gilstrap did his best to keep dry from the freezing rain determined to disrupt the annual Christmas Bird Count at Muscatatuck National Wildlife Refuge on New Year’s Day.

“It was pretty nasty in the morning,” Gilstrap said. “Actually, I saw more birds than I expected. It was a fairly good day.”

Savvy, experience, determination and the sharp eyes of wife Linda contributed to a one-day count of 38 species for the Gilstraps in the refuge, even if at times the precipitation was dense enough to prevent seeing almost anything.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]Click here to purchase photos from this gallery

Bird count day is its own holiday for serious birders, a special occasion for those who love the outdoors, admire the sweet songs and majestic flights of the world’s winged creatures and whose dedication to citizen science contributes to experts’ knowledge of population trends.

Those who have embraced bird watching with their hearts and soul have turned it into a magnificent obsession, a cross between hobby and sport.

The weather was fearsome enough that Muscatatuck Park Ranger Donna Stanley tried to warn off all of her signups with a 6:15 a.m. email. But not everyone got the message, and four hardy participants turned out anyway instead of a more typical crowd of 15 to 30.

The hardcore folks just might have ignored such an alert regardless.

“A bad day of birding is better than anything else,” said Steve Gilstrap, 72, who lives in Bedford and is semi-retired.

Going out to count

The Christmas Bird Count is a misnomer in a way. It is not a conflict with Christmas, but the National Audubon Society recognizes a block of time, this season Dec. 14 to Jan. 5, and Indiana’s Audubon Society received reports from 52 sites around the Hoosier State by that cutoff date.

A bird count was actually originated by curious hunters before the start of the 20th century, a byproduct competition by the shooter who killed the most birds, not merely saw them.

In 1900, an Audubon ornithologist named Frank Chapman came up with this alternative that he called a Christmas Bird Census. Once established, the data became an essential source of research for the Audubon Society, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and conservation groups in their study of birds and the trends affecting their species.

Brad Bumgardner, executive director of the Indiana Audubon Society, said bird counting is one of the most hands-on citizen activities across the scientific spectrum, outside of contributions made by observations of the average person to astronomy.

There are a lot of eyes on the sky in both instances, birds mostly by day, stars by night.

About 2,400 locations report in across the country with their counts their state Audubon Societies. Over time, some 413 different species of birds have been sighted in Indiana, or about 260 different kinds each year. The Indiana society states there are about 180 breeding population species.

At Muscatatuck, in an average year, those 30 birders on the Christmas count report seeing about 70 species, roughly between sunrise and dark. The heavily wooded refuge on the outskirts of Seymour on U.S. 50 is just 12.31 square miles in size. If they choose wisely, the birds can disguise their whereabouts well. Or if they show themselves, they can dart overhead quickly, outflying any automobiles or hikers.

Muscatatuck harbors about 800 cardinals, the Indiana state bird, and hundreds of sandhill cranes, Stanley said. Great horned owls are tougher to spot.

“They’re hiding,” she said.

Most birders are in for a half-day as a way to ring in the New Year, Stanley said.

“The best birding is early in the morning,” she said.

Counters meet at the visitors center. Normally, people form groups to roam the refuge, but this year, Muscatatuck urged birders to stay with them that brought them, much like attending a dance, due to the ongoing dangers of mingling in the COVID-19 era.

Much of that fear was mitigated when size of the group was stifled by the freezing rain. Stanley was somewhat surprised, however, that the quartet of energetic birders who turned in their paperwork, the Gilstraps, Mike Clay and David Carr, accounted for 55 species.

“They can go all day,” Stanley said.

Carr, who is associated with the University of Virginia but always visits relatives in the southern Indiana area for Christmas, has been on the Muscatatuck bird count since 1981.

“I always try to get out before dawn and try for owls,” he said. “None at all.”

Even though he has no direct connection to them, Carr’s best bet to see owls would have been to drive over to Seymour High School to watch one of the sports teams competing. It is not clear if an Owl mascot counts as its own species, however.

‘All about the birds’

While 70 seems like a fairly good-sized sample of birds for such a confined territory at Muscatatuck, as is often said, the world is a big place.

Just how many species of birds inhabit the planet is a question without a very specific answer. For decades, it was believed there were about 10,000 birds, and that was the figure used by birders and scientists.

However, in late 2016, just about Christmas Bird Count time, a study — and viewpoint was announced by the American Museum of National History — indicating there might be between 18,000 and 20,000 birds in the world.

The roots of this theory are a new definition of what can only be called subspecies rather than brand-new, undiscovered species of birds. This declaration was controversial in many quarters with lines drawn of accepting the concept and others ridiculing it as exaggeration.

It is not clear exactly what counts as the more authoritative number at the moment. Certainly, for those who compile life lists, this could be discouraging news that they in fact have thousands of additional birds to track down and write into their journals.

Serious birders do keep track of how many kinds of birds they see. Many report publicize their counts on eBird, an online site created by the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology in 2002.

For the average person who takes almost no note of birds other than periodically craning his neck upwards, a few recent quests in the 21st century gained mainstream attention.

First, a book called “The Big Year: A Tale of Man, Nature and Fowl Obsession,” the story of three men trying to see as many birds in a single calendar year as was possible given the constraints of their daily lives and bank accounts, was chronicled by Mark Obmascik.

This was a well-crafted suspense story followed by a movie comedy of the same name starring Steve Martin, Owen Wilson and Jack Black, which did even more to bring extreme birding mainstream.

A Big Year is basically the Holy Grail of birdwatching, and this look at it was humorized by Hollywood while also managing to capture the essence of the challenge.

The youngest chaser is quizzed by his skeptical father, asked, “What do you win? Is there prize money?” He sarcastically replies, “No, but the birdseed endorsements are huge.”

That sums it up. Birders do it because they want to, because they are moved, not because they expect a tangible reward.

What the unsuspecting viewer might learn is that to add rare birds to one’s life list and to give your all for a Big Year, you had better have almost unlimited funds and flexibility to drop what you are doing instantly and seize the moment. This is illustrated by how one birder puts the birds ahead of his marriage and how they all end up in the Aleutian Islands just because the conditions are ripe for multiple sightings.

They all know this is what it takes as New Year’s Day approaches and they commit to 365 days of madness.

“Next year is all about the birds,” the Steve Martin character said.

This was also true for Noah Strycker, who in 2015 decided to chuck his life as he knew it and somewhat on a budget try to see as many of the 10,000 known birds that year as possible. He was shooting for 5,000 and actually saw 6,042 species and wrote a book about it called “Birding Without Borders: An Obsession, A Quest and the Biggest Year in the World.” He hit all seven continents and 41 countries.

Post wild year, Strycker began an editor at Birding magazine and a bird guide in Antarctica and the Arctic.

There are places a birder can go to cram in massive numbers of species in one vacation, and Steve Gilstrap did it. It is possible to see 300 species in 10 days in Ecuador, he said.

Gilstrap has 938 bird species registered on eBird, but when asked if he has a life list, he said, “Kind of. I probably have another 500 birds that I haven’t put on.”

Sharing an interest

Gilstrap’s fourth grade teacher in Shawswick infused him with enthusiasm for birding and the outdoors.

“I started with a Golden Guide book,” he said.

Linda became his partner about five years ago because of her sharper eyes. Riding shotgun, she blurts out, “There’s something over there!” and Steve identifies the species.

“It’s something I can do with him,” Linda Gilstrap said.

While always being partial to woodpeckers, her favorite bird is the old faithful cardinal because of its bright red coloration.

“Especially in winter because it stands out against the snow,” she said. “I get tickled when people see one and say, ‘There’s a red bird.’”

Steve has been birding in Poland and Belize, as well as Ecuador, but he is very immersed in the Christmas bird counts. Besides Muscatatuck, he participated in seven others around Indiana.

But the Gilstraps don’t have to travel far to sight birds. They have numerous bird feeders in their yards, and many kinds of birds come to them.

Clay, 65, from Greenwood, eased into birding in college when he began carrying binoculars on hikes. He introduced his children to it and put up his own feeders then, but they were more lukewarm than passionate.

“They were more interested in electronics, he said.

Later, Clay joined bird hikes led by experts and found that to be fun and a way to make friends.

“You interacted with other people who were interested in birds,” he said.

In fact, he and Carr hooked up at the Muscatatuck Christmas Bird Count and became bird buds. Clay’s life list, really a North American one, is at 564.

“There are people who have more money and time, and you can see 700 species in one year,” he said.

That describes “The Big Year” contenders. Clay saw that movie and read Strycker’s book. He operates on a smaller scale, though his years amount to 40,000 miles of driving within Indiana.

Coincidentally — and this was on his mind — Clay’s first Christmas Bird Count some years ago provided remarkably similar miserable, wet weather to this year’s New Year’s Day experience.

Fascinated by flight

The climate was the same, but in the big picture, over the decades, it has not been. One of the key elements of the count these days is charting trends in the same locations to determine if climate change has affected certain populations.

While the brouhaha over the number of species debated, 10,000 or 18,000 has been an attention-getter, it may disguise the fact that the number of birds is declining because of habitat and climate change.

A National Audubon Society 2019 report suggested that Earth’s rising temperatures could put more than two-thirds of North America’s species in danger of extinction. Science magazine claimed in the fall of 2019 that the sheer number of North American birds had dropped by 2.9 billion breeding adults over the last 50 years.

“It’s hard to attribute (change) to climate change in any single year,” Bumgardner said. “It may not matter. But over 10 to 20 years.”

Over decades, bird populations rise and fall within Muscatatuck, Stanley said.

“Our woods are growing up,” she said. “Cardinals are doing well. Sandhill cranes are doing very well. If we have frozen water, we don’t get waterfowl.”

Big change on the sandhills, Carr said.

“In 1981, I never saw a crane at Muscatatuck,” he said. “Since 2011, I’m seeing them every year. It has just gotten crazy.”

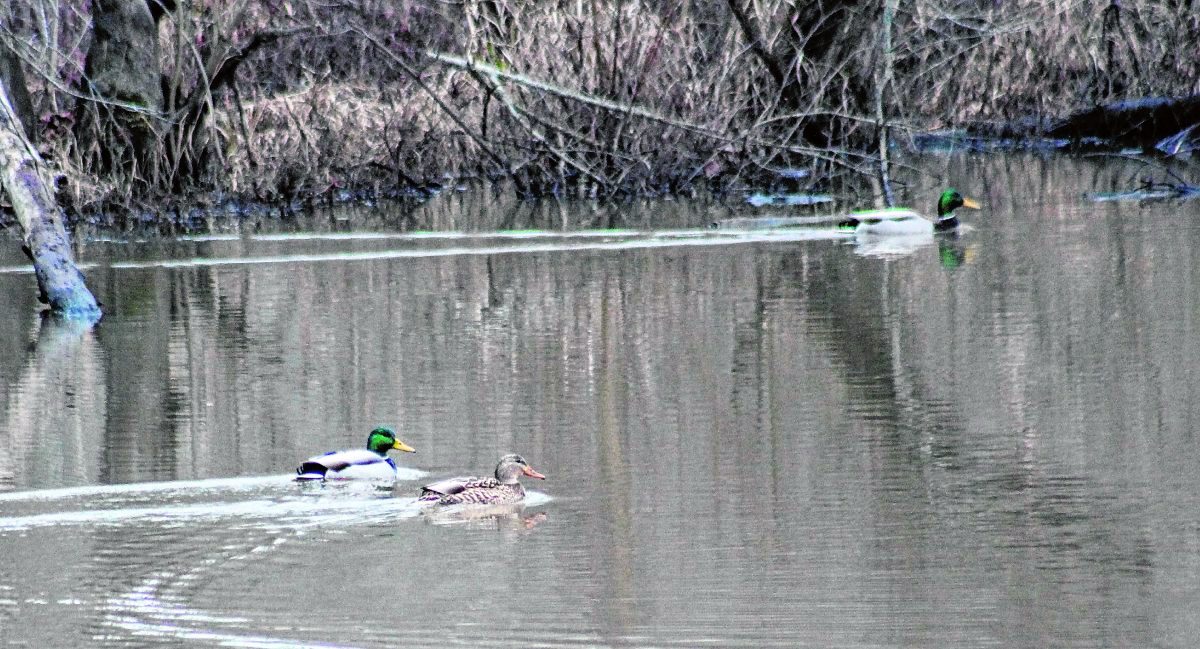

Jan. 5, a few days after the limited bird count and the last day of Indiana’s count around the state, there were few people at Muscatatuck. The water was not frozen because temperatures were in the 40s and mallards appeared quite comfortable. A woodpecker perched on a bare tree branch. A hawk whizzed overhead, alighting elsewhere out of sight.

Flitting away abruptly after a pause on the road was a bird with a red chest. It was too small to be a cardinal and not bright enough. It may have been a red-breasted nuthatch, which is Clay’s favorite.

“They’re only present in the winter some of the time,” Clay said.

This one was present for seconds.

Carr, 60, is a human scorekeeper with 40 years of Christmas Bird Count perspective at Muscatatuck. He was jokingly asked if he has seen every bird there is and replied, “Oh no, no, by no means.”

Birding and birds continue to fascinate him. It just seems basic and logical to try and see as many different kinds, at least once, that you can see.

He has seen a lot of birds, but didn’t really keep track closely until about 10 years ago. His late-in-life list has more than 700 species, his favorite being the peregrine falcon because of its speed.

“When I started birding, they were almost wiped out,” Carr said.

He also records every eagle sighting he has on eBird, too, remembering when they were endangered.

“I remember the first bald eagle I ever saw,” Carr said. “It was in the fall of 1980 on Lake Erie. I thought, ‘This is our national bird, the symbol of our country. I finally get to see this iconic bird.’”